The transition from primary school to Price’s should have ben brutal, but children are remarkably resilient, and I hardly noticed it. You went from the world of junior school where you are nurtured, called by your first name, don’t have formal timetables, and where there was little formal discipline, to one where teachers are masters in gowns and who expect you to call them “sir” and stand up when they enter a room, and who in return address you only by your surname. Daily life follows a strict timetable; I still have nightmares about forgetting which room I have to be in at 11.30. And you had to wear a uniform.

I started at Price’s in September 1969. Looking back there must have been something of a transition time when teachers who had come back from the war were starting to retire and be replaced by a younger breed, such as our form master for 1B, Charlie Tuck. We were in that hut that was split into two classrooms, and I remember we had a spectacular view of the garden next door, which always seemed to be full of flowers and birds.

None of my family had been to a school like it, so I had no idea what to expect. I remember the first day people hung around in the front playground and then when the bell rang everyone filed into assembly in orderly lines; memory though is highly unreliable and that particularly memory certainly must be faulty. I soon learned that beneath the apparent order of Price’s lay much hidden disorder. I remember being excited about having a little homework to do that first day: a little algebra: x + 2 = 3, what is x? I had seen nothing like it.

I lived quite some way away, in Bursledon, and had to catch the Hants & Dorset No. 18 bus to and from Fareham every day. Colin Fricker lived on the same council estate. He didn’t have a mother, and I didn’t have a father, but we never talked about why; boys, or at least the ones I knew, never talked about anything personal. The bus didn’t pick up other Price’s pupils until Sarisbury Green.

The first week my mother made me wear short trousers, but I quickly managed to persuade her that it apparently wasn’t the done thing. I was lucky though that I never really got bullied, although there were always a few big boys who liked to try to throw their weight around. I remember on my first day a couple of second years told me that they were “putting me in quad”. I had no idea what quad was, and had just about enough resilience to realise they had no real power over me. I still don’t know why detention was called quad. In retrospect though I am surprised by how much bullying there was, from casual to systematic, and some of it was in retrospect dangerous. Some boys had a dreadful time of being bullied, and I often wonder what happened to them. They must have utterly miserable memories of Price’s. I occasionally wonder why I didn’t I do anything to stop the bullying of others because I knew it was wrong; I suppose in part I though how can I stop it, but also a part of me was just grateful that it wasn’t me. Shame on us all. Did the teachers never suspect anything? There was still corporal punishment then, and "Tom” Hilton was reputed to have a cane in a glass cane, but I don’t remember ever hearing of it being used.

The teachers were mixed in quality, although I think generally the quality was high. I remember “Buzz” Ellis was always getting us to draw things (wattle and daub anyone?) for homework, which was probably a bit lazy of him - but then again I do remember wattle and daub construction methods more than fifty years later, so perhaps he was on to something. He also read us Readers Digest extracts about how smoking made your lungs black and tumorous. I never smoked. Who thought of these nicknames? “Smudge” Smith, “Daisy” Chapman, “Chuckles” Bowler, and “Jock” Daysh are the ones I still remember. I assume they were aware of their names, and none of them were particularly cruel. Some of the teachers must have been so young;. I don’t think “Geoff” Kerley could have been very much more than 22 - not really that much older than the sixth formers.

In the second year “Dick” Payne arrived (what were his parents thinking?). He was one of the trendy new young teachers and was very popular with many of the boys. I remember on his first day he was amazingly strict, making a big fuss because we didn’t stand up quickly enough when he came in the room. With hindsight that was the way to do it: start off being fearsome and then mellow when you have control. In contrast I remember a new maths teacher also starting in 1970; I can’t recall his name but he made the terrible mistake of starting off by being nice. That was him done for. He never managed to control the class and often it was mayhem. I found that a shame because I liked maths and wanted to learn. On one occasion there must have been so much chaos that Eric came in and gave us all a class detention picking up litter from the grounds for an hour, which struck me as unfair. I don’t think it made any difference to our behaviour and my memory is that the maths teacher didn’t come back the next year. Mr Hobson was another young teacher who managed discipline well; I remember he was always carrying a baton, which can’t be right. He taught us Latin. He had a system of testing vocabulary where you all stood in a line and if you got a word right and people before you had got it wrong, you could move up the line punching the others on the way. An effective system but I doubt it it would be allowed today. I really enjoyed Latin, and was good at it, but in the third year I chose chemistry over it. There was some choice in the curriculum, and I can see why, but I still wish I could have carried on with Latin.

I didn’t like games. This dislike is odd given that I enjoyed them at junior school, especially football. One of the highlights of the day at Price’s was playing football before assembly and at lunch break. I don’t remember any attempt being made at Price’s in formal games to make anyone other than the chosen few any better at any sport. The masters quickly decided if you had talent and if you passed their test you were in the team pool, and the rest of us had to make do with the dreaded cross-country run whenever it was wet. Neither that was there any understanding that those born late in the school year were biologically disadvantaged. How could I, born in August 1958, and with undiagnosed coeliac disease, ever compete with a six foot hulk born in October 1957? I particularly hated the horse in the gym: I had to attempt the same height as these giants among boys. No wonder I bottled out most of the time. And the CCF seemed a complete waste of time to me, prancing up and down in extraordinarily uncomfortable uniforms whose buttons had to be polished just so. I realised late in life I have never liked having to do anything I haven’t really wanted to do, and some things at Price’s were no exception.

My O-level year started in September of 1973, and 5B was based back in that hut where it all started. Our form master was Mr Briscoe, and I remember his saying in his strong Yorkshire (I think) dialect in his opening speech “now boys you have so much time yet so little time”. How true, not only of O-levels, but of life. I think of that advice often now that I am older. We had a female master, or should that be mistress, for O-level English language and literature, which was a bit of a novelty: Mrs Debunsen (I think that is the correct spelling, but it might have been De Bunsen). She was very good, and had no trouble controlling a class of boys. Perhaps we were all heeding Mr Briscoe’s advice by then. I remember we did “Richard III”, Kipling’s “Kim”, and Chaucer’s “The prologue”. I also was one of the few to take Religious Studies O-level under Mr Glynne-Howell (did he have a first name?). He had been a terrifying figure when I was young but turned out to be a fascinating one when I was a bit older. He was one of those teachers who I wished I had been able to contact before his death.

In the autumn of 1974 I started my A-levels, and at the same time Price’s started the transition to becoming a sixth form college. I was perhaps lucky in the two events coinciding because the disruption to me was minimal, and because both changes happening at the same time meant that I didn’t know what I might be missing (if anything). One consequence of the change was that I never got to be a prefect, although it is perfectly possible that because I was so small and slight I wouldn’t have been chosen, and would probably have been terrible at it.

At A level in particular there were some outstanding teachers. Geoff Kerley turned out to be great fun, and very knowledgeable about all matters of things, not just geological, and “Jock” Daysh was a wonderful teacher of maths, but Mr Chaffey (I still cannot bring myself to call him “John”, even though I was in touch with him late in his life) in particular was superb. It was he who first suggested that I went to Cambridge. I of course just did as I was told. He took me under his wing somewhat, even generously inviting me to a trip to his holiday caravan on the Dorset coast. An absolutely splendid person and teacher.

I worked hard at A-levels and found them quite easy, perhaps because I worked hard, and did well at them. I took them in the summer of 1976, that gloriously hot and sunny summer when Southampton was often the hottest part of the country. Flaming June didn’t distract me from the exams though. Although I am generally easily distracted I can be very focussed too when I really want to be, and getting in to Cambridge came before sunbathing.

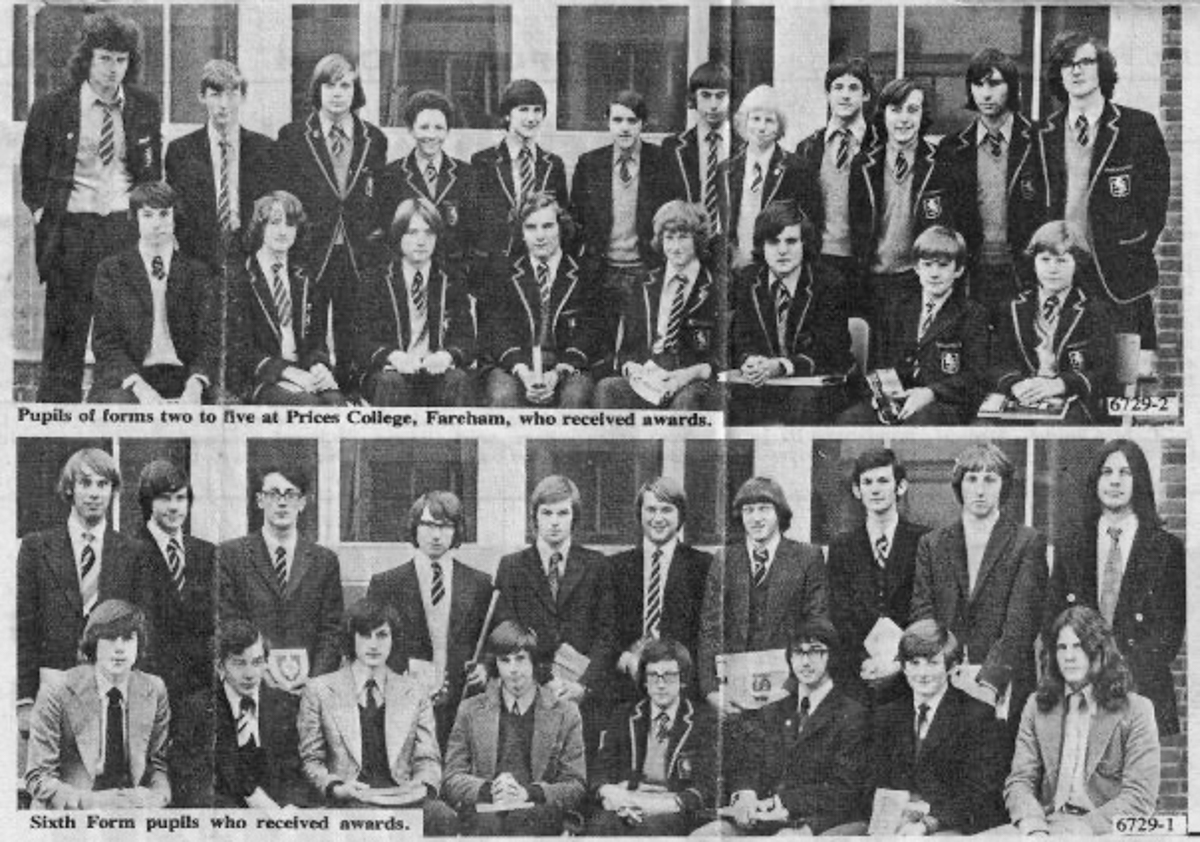

Prize giving summer 1974 after O-levels. Notice I am still wearing my Price’s jacket.

We were quite poor and couldn’t afford anything trendier

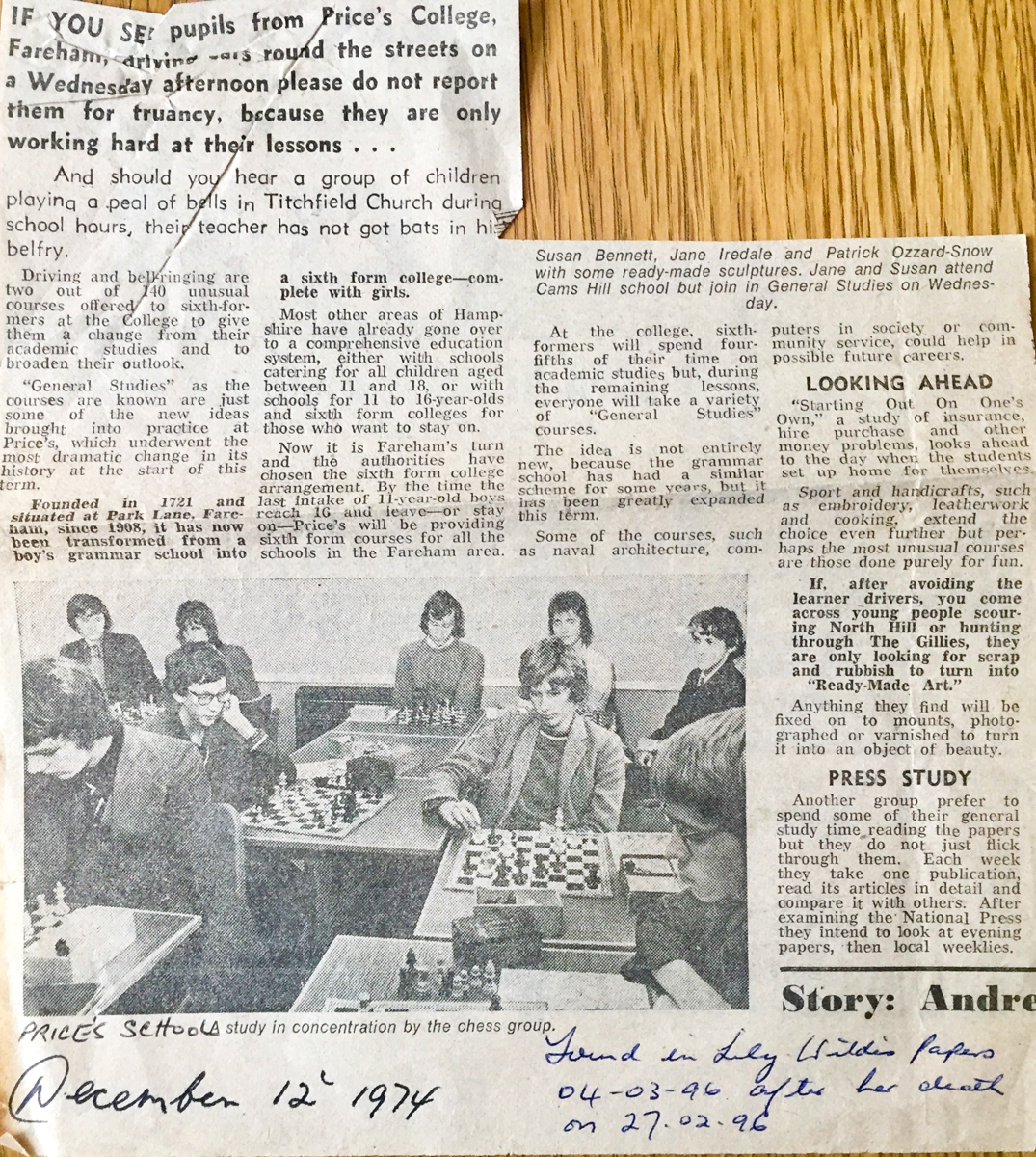

Chess lessons in the autumn of 1974, labelled by my mother and referring to my gran. Mostly I found General Studies to be a complete waste of time (did we really do potato prints?) but enjoyed chess. Peter Dear is centre, and back left Michael Comben and Kevin Garrett - they were good friends in the sixth form. There is also a chap I was very friendly with, but I don’t remember his name - Ian something, perhaps. Rob Newbury was a very good chum too but he’s not in this photograph (although is the prize giving one). Not much sign of the much-heralded girls though.

So in October 1976 I was off to Cambridge and St John’s to read Natural Sciences (Physical). I had meant to specialise in Geology but the advantage of the Natural Sciences Tripos is that you don’t need to commit to a specific subject early on. After much clambering around cliffs in the cold and wet I decided that life was not for me, and as I had always been interested in Psychology, I did that instead.

I had always assumed I was going to be an academic. In some ways I have drifted through life: teacher says take and pass 11 Plus, so I did; mother says go to Price’s, so I did. Mr Chaffey says go to Cambridge, so I did. I never at any point considered being anything but being an academic, so almost by default I stayed on at Cambridge to do a PhD.

They say psychologists are really looking for cures for themselves, and I have always had a slight speech impediment, and I did my PhD on slips of the tongue. These are when we intend to say one thing and say another. One example is a spoonerism, a (possibly apocryphal) example from the Reverend Spooner himself being “Three cheers for our queer old dean!” instead of “… dear old queen”. The Freudian slip, where we reveal our repressed thoughts, is another category, although these are in fact quite rare. One advantage of speech error research is that unlike for most of modern psychology you don’t need a lab, and the best speech errors are collected in bars.

After a couple of temporary appointments I became a Lecturer at the University of Warwick in 1985. We moved to the University of Dundee in 1996. In 2003 I became the Chair of Cognitive Psychology as well as Head of Department, and a few years later was made a Dean. I served as an assessor for the 2014 REF (Research Excellence Framework, responsible for assessing research quality across the UK every five years) for Psychology. As well as many journal articles I have written several books. I have also guided many postgraduate students to PhDs, many of them becoming academics too, producing their own PhD students. I am their academic grandfather, and quite possibly have great-grandchildren, although I am now rather out of touch.

Most of my research was on computational models of language production, and how language is affected by ageing and brain damage. The models were of the sort that are now used by “deep learning” AI - I take absolutely no credit for this advance; the learning algorithms I used were designed by others. Later on I became interested in consciousness, particularly sleep and dreams. I have retained my interest in the natural sciences, particularly weather, and too late in life realised I could combine my main interests by looking at how the weather affects human behaviour.

Students are often surprised when they start psychology by how scientific it is. Many of them think it is going to be about helping people, and then are surprised by having to sit down in front of a computer and learn how to do statistics. Computational psychology is the hardest for many undergraduates to grasp because it requires a grounding in mathematics and to some extent the natural sciences. One of the challenges of teaching is to make students realise why certain things are interesting and important, even if they can’t appreciate all the fine details.

I have flirted with standup comedy, even doing a short show at the Edinburgh Fringe. I don’t think I was particularly brilliant at it, but I wasn’t bad either, and made plenty of people laugh, and perhaps who could ask for more. I did it primarily as a confidence booster for public speaking. I was shy at Price’s, and still am, but have never felt public speaking - which is very much part of the job of being an academic - difficult. I reckoned if I could do standup at least competently I could do anything.

In 2015 I was quite seriously ill with sepsis. It’s true that in my case a close shave with death made me re-evaluate my life, and early the next year I decided to take relatively early retirement to focus on science journalism and writing. I am now Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Dundee and live in the Angus countryside on the edge of the Sidlaw Hills with Beau, my black miniature poodle. It is beautiful here, dark at night, and so peaceful. You might see me occasionally on television or hear me on radio, where I am the resident expert on the weather and how it affects us. Recent books of mine include Talking the Talk on language, The Psychology of Consciousness, and Psychology of Weather.

I have mostly good memories of Prices and I can’t imagine what would have happened if I hadn’t gone there. One of the good things about social media today is that enables school friends to keep in touch. We didn’t have that. In retrospect I walked out the school gates for the last time in the summer of 1976 and that was that. I immediately lost contact with the nearly all the friends I had been playing snooker, cards, and chess with just a few weeks before. I still find that very sad. I still think of my old friends only by their surnames: in addition to those I have already mentioned there were Cleak, Clynick, Culling, Earl, Herbertson, and Lee. I know Alan Herbert died a few years ago, and Tom Tullett had a serious biking accident a little while back. The only girls I remember were Sue Bailey and Mary-Anne Baxandall. Where are you all now?

I wish I had kept a journal while I was at Price’s: now all I have are memories, some of which might be false. I suppose virtually all the teachers I remember have since died; the only one that I am aware of being still alive is Geoff Kerley, who I gather moved back to Wales not long after I left.

I am found easily in the world and at www.trevorharley.com.